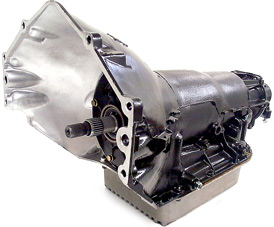

Transmissions for sale: Chevy T-400

“Where Our Customers Send Their Friends”

When most of us think of brakes we think of the items that engage and slow you down when you push the break pedal. But if you are involved in street-and-strip racing cars, perhaps with the first (that I know of) Chevy Transmissions that racing companies built a tranny brake for and you have a powerful 427″ engine in it with a traction surplus, a trans brake may be what you need.

<strong>What Is a Transmission Brake?</strong>

Available for most popular automatic transmission applications from companies like ATI for between $400 and $500, a trans-brake conversion consists of a few (reversible) case modifications and a specially modified valve body that’s equipped with an electric solenoid. A driver-operated push-button triggers the solenoid to move a shuttle valve, causing the transmission’s hydraulic circuitry to engage First and Reverse gears at the same time. If this sounds like a recipe for self-destruction, remember the car is not in motion when the activation button is depressed. With the transmission input-shaft effectively locked, the driver then mashes the accelerator pedal to the floor, giving the torque converter no option other than to slip until its absolute stall speed is reached. When the light turns green, the driver releases the activation button and the car explodes off the line. Once moving, the driver upshifts the transmission in the usual way.

Should trans-brake users be worried that the engine might over-rev and break when they mash the gas with the trans-brake button depressed? No. Although holding the pedal on the floor when the car isn’t moving yet goes against every hot rodder’s base instincts, the churning torque converter safely maintains enough resistance to limit engine speed. But for peace of mind, many users install a multi-step rev-limiter just in case, and to fine-tune the launch rpm to match track conditions.

<strong>Things to Consider</strong>

While a trans brake will typically produce a higher stall speed than foot-braking alone, it won’t transform a low-stall OE stock-er into a full race converter, so don’t look for miracles. Most manufacturers tell customers to move up to a trans brake only after they’ve already installed a torque converter that is well suited to their vehicle combination (weight, camshaft, gear ratio, traction potential, and so on). The best plan is to select a torque converter that, with the trans brake engaged, allows the motor to flash to within 200 rpm of its torque peak. There are plenty of chassis dynos in the land these days, so peak torque data is easily obtained for a modest investment.

Also, because trans-brake use requires modified staging and launch techniques on the already nerve-wracking launch pad, make the job as easy as possible. ATI suggests mounting the activation switch on the shift handle or steering wheel. With a little practice, it soon becomes second nature and you’ll discover that better reaction times are possible thanks to the consistent launch rpm versus the less repeatable method of pedal-juggling the launch stall speed. Also, most people are able to release a fingertip button more quickly than they can move their feet to lift the brake pedal and mash the gas, another reaction time benefit made possible by the trans brake.

Most importantly, a trans brake will likely subject the rear tires and suspension to increased torque. Earlier we used the term “traction surplus.” It describes the desirable condition in which full engine power can be applied to the pavement without tire slip. Installing a trans brake on a car that is already at its traction limit can cause the tires to spin and reduce performance. Buy bigger slicks!

The age-old practice of foot-braking the torque converter by applying the brakes while increasing throttle is only marginally effective. Eventually engine torque overcomes the ability of the wheel brakes to resist axle-shaft rotation, and the tires either break traction and spin or the car creeps forward before you want it to. Either way, full stall speed is not reached. When the light turns green, the engine is farther from peak torque than it could be, and performance suffers.

Trans brakes handily address this problem by uncovering every last bit of stall the converter has to offer so the engine is closer to its torque peak. That means there’s more grunt available to get you moving as quickly as possible when the race starts. As we know, the initial rate of acceleration from rest plays a vital role in cutting e.t. (elapsed time over 1/4 of a mile) Trans-brake users typically see a 1- to 2-tenth reduction in the time it takes to reach the 60-foot mark. If that seems inconsequential, remember a tenth on the starting line is roughly equal to a car length by the finish line.

I mention ATI in my article since that was my first experience with racing transmissions. ATI has been experimenting and developing all sorts of racing transmission equipment for over 35 years now. BYW: That was also my first job in the transmission business in the early 70’s. The Chevy transmissions dubbed the T-400 were the first transmissions to have a transmission break manufactured for it, soon to be followed by other transmissions made in that era.

Those were some fun days. The facts are that this is such a specialty and extremely expensive niche, not many people other than racers use this equipment, though we thought this may be interesting to you. To buy the best transmissions for sale that accommodate 99% of the majority of cars and trucks on the road, including stock and heavy duty purposes call GotTransmissions.com @ 866-320-1182 and speak to a qualified representative about which one of our transmissions for sale fits your budget and matches your best interests.